Safety planning is a critical step to finding freedom from domestic abuse, and the most effective safety plans include the entire family. For many survivors, this means finding a path to safety that accommodates their pet. In fact, half of all pet-owning survivors report that they would not consider entering a shelter if they couldn’t take their pet with them. If you’re an advocate that assists survivors with safety planning, use the following guide to ensure that your safety plans are pet inclusive.

Establish Proof of Ownership

Helping survivors establish legal ownership of their pets is an important step to ensuring futures free from abuse and coercive control. Documents like veterinary records, adoption paperwork, and pet licenses help establish ownership. If your client already has these documents, advise them to keep copies in a safe place. For pet owners without documentation, you can help them build a paper trail by setting up a vet appointment and establishing pet care under their name.

Know Where to Go

If your client needs to leave home in a hurry, where will their pets go? Help survivors identify a friend or family member who can care for pets in an emergency or use domesticshelters.org to locate a shelter with pet options. While some shelters allow pets to live on site with their owners, others may provide off-site services like temporary boarding or foster care.

If there are no pet-friendly shelters in your community, RedRover may be able to help. RedRover Safe Escape grants help cover the cost of temporarily boarding a pet while their owner is in a domestic violence shelter. Visit RedRover.org to review eligibility requirements and learn more.

Create a Pet Go-Bag

Prepare survivors for a quick departure by packing a pet go-bag with essential items. Include pet food, medications, veterinary records, ID tags, a leash, collar, carrier, and their pet’s favorite toys. Store these items with a trusted friend or in a secure location to ensure they are readily available when needed.

Update the Pet's Microchip

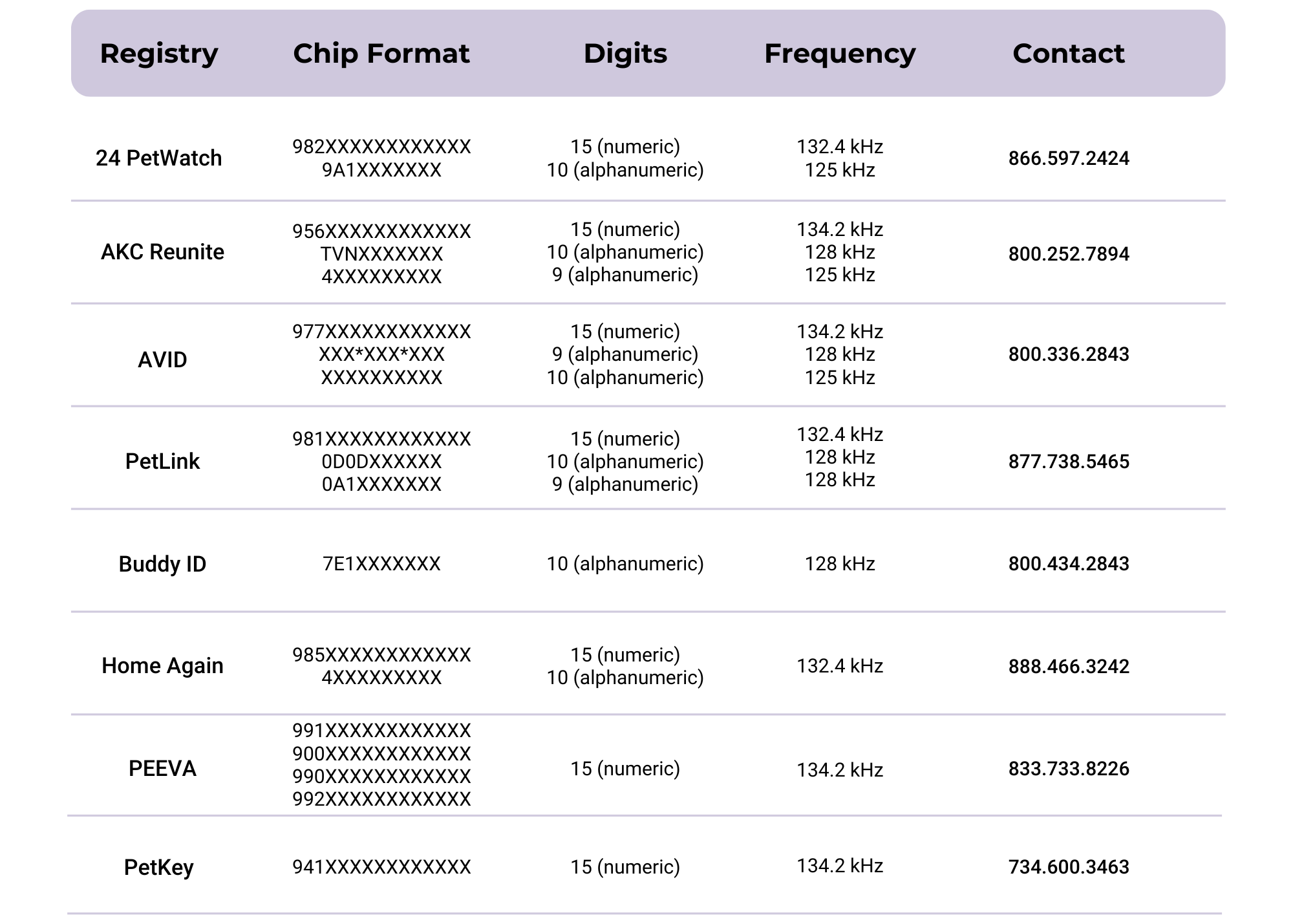

Microchips are an important safety feature that help reunite lost pets with their owners. Typically inserted under a pet’s skin near their shoulders, microchips give off radio waves that can be detected by a microchip scanner.

These scanners are available at most animal shelters and veterinary clinics. Once you’ve confirmed that a pet has a microchip, identify the corresponding registry using the table below.

Microchip information should be updated regularly to ensure it is correct. When working with survivors of domestic violence, make sure to remove the abuser from the pet’s contact list and place a “do not disclose address” notice on their account.

Unlike a microchip, GPS collars and devices like Airtags are able to provide real-time location information for pets, and by extension, survivors. Make sure your client removes these items from pets before leaving home.

Build a Safe Routine

Help survivors establish a safe routine for their pets, whether they are sheltering with you or elsewhere. Identify safe routes for dog walks and encourage them to find a walking buddy. To prevent pets from being stolen or harmed, avoid leaving them outside unattended. Instead, keep pets indoors or behind secure privacy fencing.

Change Care Providers

Keep pets and survivors safe by avoiding places the abuser may expect to find them. If the pet visited a particular veterinary clinic, groomer, or doggy daycare, work with the survivor to find new providers in new locations. Make sure these providers know who is approved to pick up the pet from appointments and who is not.

Seek a Protective Order

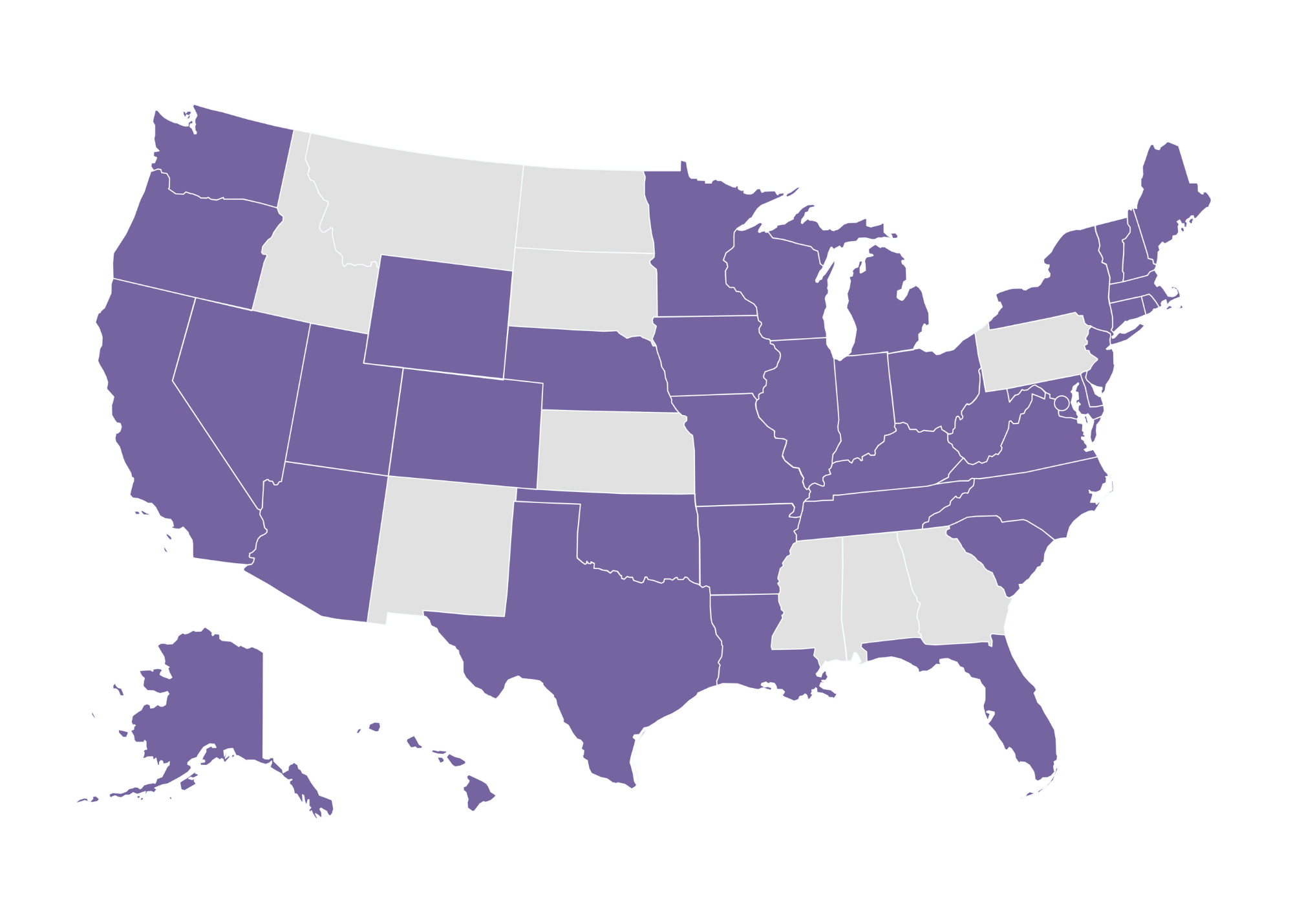

As of October, 2024, there are 40 U.S. states with laws that allow pets to be included in domestic violence protective orders. Use the map below or visit the Animal Legal and Historical Center to learn more about laws in your state.

Even if your state does not explicitly include pets in protection laws, judges may still issue protective orders for pets under “catch-all” provisions. These provisions allow judges to include whatever conditions are reasonable and necessary to ensure the victim’s safety.

If your client was forced to leave a pet behind with an abusive partner, taking active steps to help them reclaim their pet may prevent them from returning to a dangerous situation. Consider reaching out to local police or humane law enforcement to see if they can help your client safely retrieve their pet.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Incorporating pets into safety planning is an essential part of supporting survivors of domestic abuse. By addressing the needs of both people and their pets, advocates can provide more comprehensive assistance that not only safeguards the well-being of animals, but encourages more survivors to seek help.

As we continue to refine our approaches to safety planning, let us remain committed to including every member of the family, recognizing that true safety and recovery come from addressing all aspects of a survivor’s life. By doing so, we can foster more inclusive and supportive environments for those seeking freedom from abuse.

Want to learn more? Check out our webinar, “Safety Planning with Pets” with the Arizona Coalition to End Sexual and Domestic Violence.

Updates

2.20.25 In December, 2024 Pennsylvania enacted H.B. 1210, which amends Pennsylvania’s Protection from Abuse Act to give judges the ability to order a defendant to refrain from possessing, abusing or harming a petitioner’s companion animal.

Danielle Works is the Community Engagement Manager for RedRover. With more than 10 years of experience in animal welfare, Danielle consults with shelters throughout the country to identify collaborative solutions for pets and owners in crisis. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Biology from Willamette University in Salem, Oregon.